Writing this post was really weird and frustrating: I must have scrapped 3 or 4 full-length drafts, each focusing on a different nuance of my intended subject before I finally arrived at this one. I had initially intended to write about revisionist claims regarding the Taj Mahal – a generic rebuttal against the underlying principles of said claims. Nothing too glamorous or fancy, just a straightforward analysis of why they are wrong, yet garner so much support (much like my previous post on the stabbed-in-the-back myth). However, as I explored the claims made by supremacist politicians and revisionist authors, one text stood out as the epitome of everything I despise about revisionist history. Indian author P N Oak’s book, “The Taj Mahal is a Temple Palace”, is pretty much what the name suggests, an alternative theory claiming that the Taj Mahal was an appropriated Hindu temple rather than a Muslim mausoleum constructed from ground up. Now don’t get me wrong – challenging orthodox historical opinions is a necessary facet of historical discourse. Oak’s book, however, is the exact opposite – it’s neither “historical”, nor is it a “discourse” in so much as it is a laundry list of inaccuracies and misrepresentations. The generalizations, cherry-picked evidence, factual distortion and outright Hindu supremacism that Oak purveys under the veneer of “challenging the orthodox view” is a mockery to the discipline that I have come to love and appreciate. This post will thus be my rebuttal against his theories, and the reasoning behind the conclusions that I have reached.

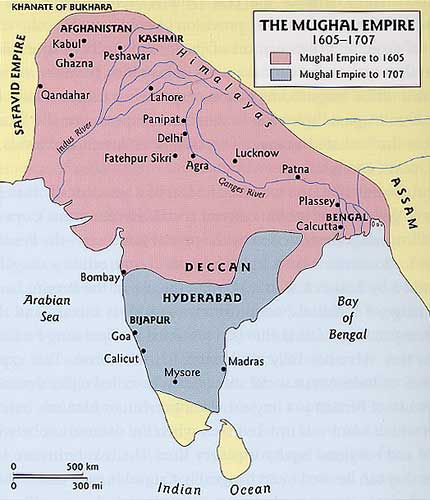

To provide some background: I am sure that most of us know about the Taj Mahal. Per the widely accepted historical record, the Taj Mahal was commissioned by Mughal Emperor Shah Jahan as a tomb for his favourite wife, Mumtaz Mahal. The Mughal Empire that he ruled was founded by a warlord called Babur, who expanded into India after conflicts with other Uzbek warlords drove him from Central Asia. Under successive emperors, the Mughal Empire held dominion over most of Central and Northern India from 1526 to 1857. Shah Jahan was the 5th Mughal emperor and ruled from 1628 to 1658.

The opposition to the widely accepted historical narrative about the Taj Mahal was articulated by Oak in around 1965. As described in the introduction, he advanced the theory that the Taj Mahal was a Hindu temple seized by the Mughals and converted into a tomb. His theory quickly gained traction amongst Hindu nationalist circles, which have recently taken to denouncing the Taj Mahal as a coopted Hindu temple. Even some politicians (mostly of the nationalist Bhartiya Janta Party) have given official sanction to his theories[1].

To those who have not read Oak’s book, here’s a summary of how he arrives at his thesis. He first argues that Shah Jahan could not have possibly built the Taj Mahal, due to his chaotic rule and his inherent “lack of soft feelings”. In fact, he argues that Mughals could not have built anything due to the ineptitude and corruption that characterized their rule. As such, Oak believes that its much more plausible for the Taj Mahal to be a Hindu temple, due to the prevalence of Hindu motifs in the architecture of the structure and the history of the land on which the structure was built. Oak concludes by admitting that the evidence for his theory isn’t decisive but pins the blame for that on a mix of “the Mughals fabricating history and burying evidence of the temple’s presence”, “foreign revisionism”, and even suppression by the Indian government.

Oh boy. This is going to be a long one.

Part 1 – The bad, bad Mughals

To forward his first argument, Oak argues that the Mughals were bad at pretty much everything – their conduct as rulers, their management of financial affairs, and even at being moral human beings. He writes that Shah Jahan’s reign in particular was a period of chaos, so much so that nothing could have plausibly been built. To back this claim, Oak points to the war of succession between Shah Jahan’s sons that took place after his illness in 1658, and thus claims that “if (his) reign had been the golden period that it is wrongly described to have been, such utter chaos and countrywide rebellion would never have erupted when he fell ill”. Therefore, Oak alleges that the Mughal Empire simply did not have the capacity to foot the bill for the Taj Mahal, let alone to function as a stable empire.

There are several problems with this theory. For one, Oak uses a conflict over succession at the end of Shah Jahan’s rule as evidence for “endemic problems” during his tenure. However, Oak does not show how a war of succession, a conflict motivated by political rivalry and a dispute over the throne, proves the endemic economic problems that he alleges of Mughal rule. In fact, even kingdoms (relatively) unmarred by economic problems were prone to wars of succession due to the ambition and rivalry amongst claimants. Alexander the Great’s empire, for example, fragmented as he died without designating a successor amongst the myriad of claimants in his court. More recently, the Spanish war of succession from 1701 to 1714 occurred due to the competing claims of Holy Roman Emperor Leopold I and the French King Louis XIV. The element of socioeconomic misrule simply does not explain a conflict over who gets the throne – Oak would be hard pressed to say that Louis XIV pressed his claim over Spain to remedy an ailing economy, or that Alexander’s ministers went to war to alleviate social problems. The proof for an economic dimension also isn’t present in the cases that Shah Jahan’s sons presented in order to gain support for their individual claims to the throne. In a letter to the Raja of Mewar (a Mughal vassal), for example, Prince Aurangzeb (one of the claimants) asks for the Raja’s support by promising to not interfere in Mewarese internal affairs if he were to seize the throne[2]. The letter is oriented around promising autonomy and safeguarding sovereignty – and does not make any mention of improving the economy or restoring order, which we would have expected if the conflict was triggered by socioeconomic grievances. Thus, if we take the Mughal war of succession as an indicator for the status of Mughal rule under Shah Jahan, we can only reasonably conclude that political rivalry and intrigue was rife amongst the emperor’s sons – but we cannot infer the character of his rule from this conflict alone

What then was the nature of Mughal rule? Let’s focus on the economic state of India under the Mughals. I will not be providing a full analysis of India’s economy, as there are a large variety of factors that influenced economic development and expansion during the Mughal era. However, since Oak is insinuating the incapability of the Mughal state to operate coherently, I will explicitly focus on the role that Mughal emperors played in India’s economic development, for better or for worse. And from the evidence that we currently possess, the former appears to more likely than the latter – India’s economy as a whole improved while under Mughal rule, partly due to the implementation of various reforms by Mughal emperors which facilitated the expansion of India’s agricultural and manufacturing sectors. For example, emperor Sher Shah Suri (1538-1545) implemented a uniform currency[3] and started a series of agricultural reforms that were furthered by his successors, such as the construction of state-funded irrigation systems that boosted agricultural output[4]. Similarly, under emperor Akbar (1556-1605), the Mughal state provided tax breaks to farmers that expanded their cultivated land[5]. As a result, per-capita agricultural output in the Mughal Empire (in the 17th century at least) was higher than that of Europe[6]. These improvements were also registered in manufacturing. By the 18th century, Mughal India accounted for 25% of the worlds industrial production[7] due to a variety of economic initiatives enacted by various Mughal rulers. The emperors Jahangir (1605-1627) and Shah Jahan, for example, financed textile workshops under the kharkhana system, where workers and craftsmen (much like their agricultural counterparts) operated with relative stability[8]. As a result, the textile industry flourished, so much so that textile imports from India constituted a staggering 95% of British imports from Asia in the late 17th Century[9]. Overall, the weight of evidence we have thus suggests that the Mughal economy (at least up until the death of Shah Jahan and the formative years of his successor) was doing fairly well.

To Oak’s credit, Shah Jahan can be blamed for a number of economically unsound policies. His campaigns against the Deccan kingdoms, the Safavid dynasty and the Portuguese combined with his exorbitant building projects led to a substantial increase in taxation. In the long term, excessive taxation prevailed under Mughal Emperor Aurangzeb, (his successor) which provided the impetus for peasant unrest and rebellion towards the end of his rule[10]. The financial burdens of Shah Jahan’s wars (which were furthered by Aurangzeb) also alienated influential Indian merchants and bankers, thus laying the groundwork for the economic decline of the Mughals in the latter half of Aurangzeb’s rule[11]. However, it would be ridiculous to suggest that the Mughal economy under Shah Jahan was inherently nonfunctional. After all, from all the examples that have been detailed in the earlier paragraph, it becomes apparent that the Mughal economy was still flourishing during the period of Shah Jahan’s reign (The mid 17th Century). Hence, we can plausibly say that Shah Jahan’s economic blunders had a long-term effect, which came to light alongside other political conflicts during the reigns of his successors. However, the evidence we have about the Mughal economy does not back Oak’s claims about the chaos and corruption during Shah Jahan’s reign.

But here’s the biggest problem. None of this comes out in Oak’s text – nothing regarding the evaluation of the Mughal economy, or perhaps a nuanced analysis of Shah Jahan’s economic policies. Rather, what we get are sweeping statements, such as “had (Shah Jahan’s) rule been wise and benevolent the news of his illness would have evoked a touching response from his subjects. Far from that even his own sons rose in open revolt – what greater indictment could there be of his misrule!”. Oak does not bother to qualify his analysis of the Mughals, instead relying on nice-sounding statements that belong in a fable more so than a serious historical text. What exactly is a “wise and benevolent” ruler? In what manner did the Mughal Empire’s success depend on the personality on its leaders? Were Shah Jahan’s tax collectors, bureaucrats, vassals and merchants (the people most responsible for the collection of revenue for the Imperial treasury) really that reliant on the “wise-ness” and “benevolence” of their leader? These are major assumptions behind Oak’s thesis, none of which are given a solid justification or are backed by evidence. Therefore, we can credibly say that Oak’s claim regarding the Mughals not possessing the financial resources to construct monuments like the Taj Mahal is thoroughly baseless.

Oak then argues that even if the Mughals had a functioning economy, the Taj Mahal could not have been built as a monument because he was “lacking in soft feelings”. Here, Oak is pretty much appealing to the reader’s emotions. Surely a tyrant like Shah Jahan could not have possibly appreciated art, or valued architecture enough to commission the building of massive monuments? The problem is that this is the sum of Oak’s logic to further this argument. Shah Jahan did carry out several questionable acts, such as murdering rivals within his family when he ascended to the throne[12]. However, Oak does not prove the correlation between the atrocities of an emperor and said emperor’s architectural patronage or appreciation. In fact, the historical record shows that this correlation may not be entirely accurate. The Mongol Khans, for example, were not well known for their appreciation of human rights (to put it mildly). Yet, leaders like Kublai Khan and Ogedei Khan were well known patrons of religion, arts and the sciences[13], with numerous academies and schools personally commissioned by official decree. Even Adolf Hitler was regarded by his chief architect, Albert Speer, as a connoisseur of architecture with an eye for commissioning monuments that glorified his rule[14]. As such, Oak’s argument simply is not good enough for me. His attempt at linking Shah Jahan’s “lack of soft feelings” to his (in)ability to commission the Taj Mahal is at best a statement that may sound intuitive but is disproved almost immediately with proper analysis.

Now if you have read my post up until this point, you must surely be wondering how much worse Oak could get. Not to worry – he definitely does; in his last argument against the Mughals, Oak claims that even if the Mughals had the resources and the motivation (on Shah Jahan’s part) to build the Taj Mahal, they were “not refined enough” to design and construct such a monument from scratch. He argues that “with the start of the Muslim invasions (of India), education and training in all arts (in Muslim regions) came to a dead halt”, thus preventing any subsequent Muslim kingdom from developing architectural and artistic sensibilities. To back this assertion, Oak further claims that every instance of “Islamic” art and architecture in Asia was created by “Indian Kshatriyas (members of the Hindu warrior caste) who ruled West Asia”, whose collapse spelled the permanent end for “the pursuit of art and education” – leaving Muslim warlords to claim ownership of their works, without constructing any of their own. According to Oak, the Islamic kingdoms that emerged from the Hindus’ collapse soon turned to “plundering the riches of India”, where their warmongering and brutal conduct inhibited their “artistic sensibilities” even further. Thus, Oak argues that the Mughals could not have possibly been trained in the arts due to their inherent “unrefined-ness” and barbarity.

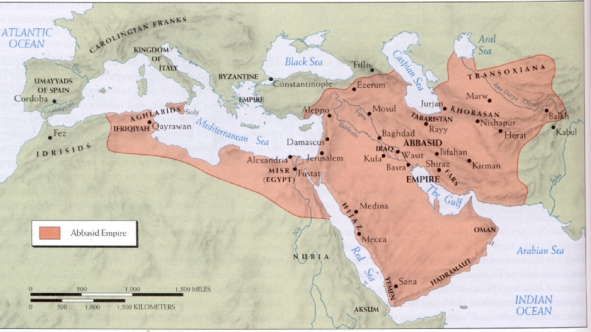

The problem with this argument is that Oak establishes yet another binary, this time pertaining to the history of West Asia. He pretty much argues that in the past (he does not specify the exact time frame), Hindus ruled the Middle East and all was good. As a result of their (unexplained) fall, however, the Middle East plunged into a purgatorial era, which incentivised Muslim conquerors to ransack India. But this is not corroborated at all – and it simply does not make logical sense. According to Oak, the Middle East descended into anarchy and turmoil after the downfall of the ruling Hindu kingdoms. However, what would then explain the existence of the Abbasid Caliphate, for example, which was responsible for facilitating the Golden Age of Islam[15]? Why did our mysterious Indian rulers fall and why are they not referred to in any source that we have that talks about the history of the Middle East? These questions are not answered yet are assumed to be the truth by Oak as he argues against the Mughal’s flair for architecture, or their supposed unrefined-ness. Honestly, I could go in detail about each of his claims regarding the supposed “Hindu” history of the Middle East and show how that is systematically wrong. But to any unbiased reader, it should become obvious that from the weight of evidence we have about the history of that region and the utter lack of supporting detail offered by Oak, his claims should be disregarded as poorly conceived fiction.

The bigger issue with this argument is that Oak is forwarding a simplistic theory about the Mughals. He lumps every incursion by every Muslim king into India together, to prove that every “Muslim marauder” invaded India with the intention of plunder and destruction. To Oak, therefore, every “Muslim” king is guilty of the inherent destructiveness and unrefined-ness that he alleges of other historical Islamic kingdoms. This is bad reasoning – and is in a sense factually inaccurate as well. Shah Jahan’s ancestor, the warlord Babur, may have started his campaign in India by plundering and raiding Hindu territories. However, in the long-term Babur and his descendants settled down to govern their conquered domains, as evidenced through their economic policies and reforms which indicates a Mughal governance more nuanced than what Oak claims. Even if we give Oak some leeway by accepting his historical fiction as fact, his theory just does not hold up once we discard the generalisations that form the premise of his argument.

Therefore, in my opinion, none of Oak’s arguments regarding the inability of the Mughal Empire during Shah Jahan hold any weight. The Mughal Empire during his rule was almost certainly not a hotbed of fiscal incompetence, empty treasuries or the wanton chaos that Oak alleges. His subsequent arguments alleging architectural incompetence and a sadistic emperor lack even the most basic of evidence needed to qualify his claims as a historical argument. Therefore, if we look back at his overall thesis, Oak has not sufficiently proved as to why we should discount the current narrative placing the Mughals as the builders of the Taj Mahal – and on this ground alone, his arguments should be discounted. But for the sake of the argument, I will go into greater depth into how the Taj Mahal is definitely not a redecorated Hindu temple in my next post.

References:

[1] How Hindu Nationalists Politicized the Taj Mahal. (2017, November 27). The Atlantic. Retrieved from https://www.theatlantic.com/international/archive/2017/11/taj-mahal-india-hindu-nationalism/546374//

[2] Khan, I. A. (2001, January). State in the Mughal India: Re-Examining the Myths of a Counter-Vision. Social Scientist, 29(1/2), 32-32. doi:10.2307/3518271

[3] Ali, M. A. (1978). Towards an interpretation of the Mughal Empire. Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain & Ireland, 110(01), 38-49. doi:10.1017/s0035869x00134215

[4] An Atlas and Survey of South Asian History. (1995). 100. doi:10.4324/9781315706429

[5] Kozlowski, G. (1995). Imperial Authority, Benefactions and Endowments (Awqāf) in Mughal India. Journal of the Economic and Social History of the Orient, 38(3), 355-370. doi:10.1163/1568520952600425

[6] Suneja, V. (2000). Understanding Business: A Multidimensional Approach to the Market Economy. Psychology Press, 13. Retrieved February 21, 2018.

[7] Parthasarathi, P. (n.d.). Historical Issues Of Deindustrialization In Nineteenth-Century South India. How India Clothed the World: The World of South Asian Textiles, 1500-1850, 415-436. doi:10.1163/ej.9789004176539.i-490.115

[8] Khan, H. A. (2015). Artisans, Sufis, shrines: colonial architecture in nineteenth-century Punjab. London: I.B. Tauris.

[9] Bowen, H. V. (2004). Bullion for goods: European and Indian merchants in the Indian Ocean trade, 1500–1800. The Economic History Review, 57(4), 800-801. doi:10.1111/j.1468-0289.2004.00295_27.x

[10] Malik, J. (2010). Islam in South Asia: A Short History . Journal of Islamic Studies, 22(1), 93-95. doi:10.1093/jis/etq069

[11] Leonard, K. (1979). The ‘Great Firm’ Theory of the Decline of the Mughal Empire. Comparative Studies in Society and History, 21, 151-167. Retrieved February 21, 2018.

[12] Findly, E. B. (2001). Nur Jahan: empress of Mughal India. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

[13] Raina, R. (1993). Frozen in Time: Ancient Skills of the Mongols. India International Centre Quarterly, 20(3), 79-94. Retrieved February 22, 2018.

[14] Speer, A. (1970). Inside the Third Reich.

[15] Brentjes, S., & Morrison, R. (2010). The New Cambridge History of Islam

One thought on “The Taj Mahal – Part 1”