Part 1 can be found here

In the second half of his argument, P N Oak attempts to substantively prove that the Taj Mahal was constructed as a Hindu temple/palace before it was co-opted by the Mughals. Oak forwards 2 main arguments to defend his theory:

- The historical record and the architecture of the Taj Mahal proves that that it was a co-opted Hindu temple/palace,

- The absence of decisive evidence to prove Oak’s claims is not reason enough to discount his argument, due to the “historical revisionism” (ironic, I know) on the part of both the Mughals and Indian academics afraid of the truth.

In my last post, I claimed that Oak’s writing was in practice a laundry list of generalisations, cherry-picked evidence, factual distortion and even outright Hindu supremacism. To a certain extent, I proved the existence of these traits in the first half of his argument. Unfortunately, these traits continue to resonate in the second half of his argument to a more pernicious degree than the first.

Part 2: The historical record

Oak first argues that the Taj Mahal was a forcefully co-opted Hindu temple/palace due to the ambiguities inherent in the historical record. For his argument, Oak primarily relies on the Badshahnama, a chronicle of Shah Jahan’s reign written by his court historian, Abdul Lahori. In describing the construction of the Taj Mahal, the Badshahnama describes the purchase of land from one of Shah Jahan’s vassals, the Rajput Raja Jai Singh of the Kingdom of Amber. The land housed one of the Raja’s mansions, which had been built by his great-grandfather and had remained in the Singh family until its purchase and (presumed) demolition by Shah Jahan in order to make way for the Taj Mahal[1]. As such, Oak argues that the Taj Mahal in its current form is in fact a modified version of the original Rajput palace, as it’s demolishment is not explicitly mentioned in the text. Moreover, Oak alleges that the forced co-option of a Hindu temple to serve as a Muslim mausoleum was in line with Shah Jahan’s oppressive and exploitative policy towards Hindus, thus lending further credence to his theory.

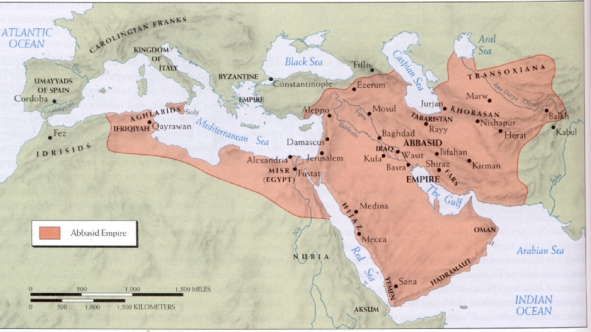

Debating the exact interpretation of the Badshahnama would prolong this post by a few thousand words. Whether the text was meant to be interpreted literally or with certain context-specific assumptions is an ongoing historical debate. However, established historians and architects alike have already offered the most direct rebuttal to Oak’s theory which proves that his interpretation of the Badshahnama is incorrect: If the Taj Mahal were in fact a co-opted, redecorated Hindu temple, the architectural style of the building as a whole would be primarily “Hindu”. However, this simply is not the case. As historians such as Dirk Collier and Ebba Koch have argued, Mughal structures such as the Taj Mahal reflect a uniquely “Mughal” architectural style that incorporates Hindu as well as Central Asian, Persian and Ottoman influences and traditions[2]. For example, the Taj Mahal incorporates hierarchical symbolism – a distinctively Hindu architectural style that highlights contrasting colours in order to distinguish the presence of different castes in the architecture of the building itself. However, the Taj Mahal also places a strict premium on preserving symmetry (which is evident to any visitor to the Taj Mahal complex) which is simply not present in a systematic and contiguous manner in Hindu temples of the era[3]. In response to this argument, Oak attempts to contrast the photos of the Taj Mahal with other Hindu temples in order to highlight their similarities, but that simply is not good enough. At best, these comparisons prove that the Taj Mahal’s architecture was imbued with “Hindu” characteristics – which does not disprove the main argument that the Taj Mahal was structure built from the ground up with a style that incorporated Hindu symbolism and motifs. For Oak to get away with his argument, he would have to prove that the Taj Mahal was entirely Hindu in its architectural makeup, which he has failed to do.

The more problematic aspect of this argument lies in the second assertion that Oak makes: that the forced appropriation of a Hindu temple was in line with Shah Jahan’s existing policy towards his Hindu subjects. Oak does not offer much analysis to back up his claim, and instead simply asserts that the “general Muslim usurping of tradition in India” and Shah Jahan’s desire to “impoverish wealthy Hindu families” give credence to him forcefully appropriating Jai Singh’s property. To put it another way, Oak does not really justify his interpretation of Shah Jahan’s policy towards his Hindu vassals beyond asserting that “the Mughals, being Muslims, must have naturally oppressed the Hindus”.

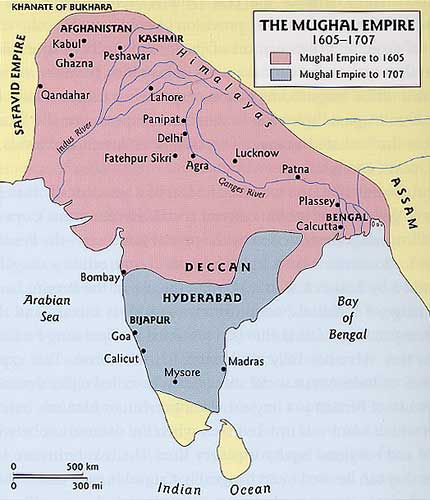

If we push past the generalisations, however, one would discover that Shah Jahan’s policies towards his Hindu subjects were a mixed bag. On one hand, the evidence suggests that on paper, Shah Jahan reversed the policies of religious tolerance towards Hindus by his grandfather, the famous Emperor Akbar. For example, he issued an edict in 1632 prohibiting the construction of new Hindu temples and ordering the demolishment of those currently being built[4]. Court customs were Islamicized and Hindus were forced to adhere to a dress code that segregated them from Muslim courtiers[5]. Similarly, hostile non-Islamic kingdoms that submitted to Shah Jahan were often forced to choose between Islam or the sword. However, it seems that some of these policies were half-heartedly enforced or were retracted after a while. For example, in 1645, the Mughal prince (and future emperor) Aurangzeb converted a Hindu temple constructed by a rich merchant, Shantidas Javeri, into a mosque[6]. However, Shah Jahan intervened in favour of Shantidas Javeri by ordering Aurangzeb to restore the temple and its plunder to the Hindu community in its entirety[7][8]. Similarly, Shah Jahan’s Hindu vassals were allowed to operate with relative freedom and continued to occupy numerous powerful posts in the Mughal bureaucracy by serving as governors and generals in Shah Jahan’s armies[9]. In fact, as I pointed out in my previous post, Aurangzeb famously attempted to obtain Rajput backing for his claim to the throne by promising to continue to respect their autonomy as vassals, which implies that Shah Jahan’s Hindu subjects were used to a similar level of independence while under his rule. As such, Shah Jahan’s “anti-Hindu” policy does not appear to be consistent in its application and enforcement, which to me is strong proof that Shah Jahan was not entirely “anti-Hindu”.

So what would be the best reconciliation of these seemingly contradictory religious policies? In my opinion, Shah Jahan’s religious policies appear to have been driven by the need to placate different groups in Mughal society. The initial edicts suppressing the practice of Hinduism could have been enacted on paper and enforced to a degree to placate the powerful Muslim imams and vassals who desired for the Mughal Empire to become more “Islamic” in character after the tolerant regimes of Akbar and Jahangir[10]. The enforcement of Islamic customs in court would have left a strong impression on the imams and courtiers in the Mughal capital, and the initial wave of destruction would have solidified their approval of Shah Jahan. However, if these policies intruded on the Shah’s powerful Hindu vassals or influential merchant communities, they would simply not be enforced. This in part explains the subservience of the Shah’s Rajput vassals: under Shah Jahan, the Rajputs continued to provide tax and levies for the Mughal armies, while serving in the imperial army as generals and commanders[11]. Unlike under Shah Jahan’s successor Emperor Aurangzeb, who provoked a Rajput revolt by clamping down on the religious liberties and powers of his Hindu vassals[12], Rajput leaders such as Jai Singh remained largely loyal to the Mughal state under Shah Jahan. Similarly, Hindu merchants continued to bankroll Shah Jahan’s expensive campaigns in the Deccan and even his military campaigns against Hindu opponents, and only cut off credit to the Mughal state once Aurangzeb materially infringed on their religious liberty and freedom of action[13]. Therefore, we can say with reasonable certainty that Shah Jahan’s religious policies may have appeared potent on paper so as to pander to his orthodox Muslim base but were probably restricted in practice so as to retain the support of the powerful Hindu merchants and vassals kings that the Mughal state heavily relied on.

This takes us back to the original question: is it possible for the Taj Mahal to have been forcefully converted from a Hindu temple into a Muslim mausoleum if we set aside the architectural evidence to the contrary? From my argument above, I believe that the possibility for this is minute. From the evidence that I have put forward, the forceful co-option the property of a Hindu king appears to be at odds with the principle of Shah Jahan’s policy towards his vassals. As such, Oak’s argument alleging the hostile takeover of a Hindu temple does not really stand.

Part 3: Evidence is overrated

In one of my points in my previous post regarding the Taj Mahal, I elaborated on why Oak’s arguments rub me the wrong way. Let us take for example the argument that we just discussed: Oak does not bother to provide even a cursory analysis regarding Shah Jahan’s religious policies, and instead merely panders towards the stereotype of the “evil Hindu-hating Muslim” with assertions that belong more so on a far-right Hindu supremacist website than on a serious historical text. However, the final claim that he makes to salvage his argument in his book trumps the fallacies, generalisations and poor argumentation that he has made thus far.

In the penultimate chapter of his book, Oak attempts to pre-empt professional critique, particularly with regards to his lack of positive evidence towards his theories. In response, Oak argues that the presence of decisive evidence in favour of his theory is not necessary, because “murderers and cheats (have been) convicted around the world on the basis of negative evidence”, with the “tell-tale details (evidence proving their actions) being discovered later”. In addition, Oak alleges that his theory can only be proven with negative evidence due to the burial of evidence and historical revisionism exercised by Mughal authorities and an “embarrassed” Indian government.

From Oak’s argument, it becomes apparent that he has failed to understand the concept of “proof” – in both the context of criminal justice and historical discourse. For one, Oak is literally making the argument that a conclusion derived from negative evidence i.e. that event A must have taken place entirely because event B did not is valid logic, when it just is not true. Setting aside the rather obvious miscarriage of justice that Oak refers to in attempting to justify his logic, disproving an opposing narrative does not automatically justify ones’ version of events, as history is not a zero-sum game. Historical events and narratives are not taken as proof just because they are “the best explanations available”, but because they are the “best explanations available that are backed by historical proof”. Disproving an established theory explaining the existence of humans in pre-historic America, for example, does not automatically legitimise me to claim that aliens populated America with human beings, regardless of how plausible (yet unsubstantiated) the argument may be. In the same fashion, disproving the established narrative about the Taj Mahal does not automatically legitimise the counter-narrative of a co-opted Hindu temple, as much as it does not allow me to claim that the Taj Mahal was built by aliens instead. An alternative historical theory must be proven with positive historical evidence and logic if it is to occupy the space of a disproven, mainstream theory, which is a notion that Oak is unable to grasp.

Oak also has not credibly demonstrated why, or how Mughal authorities and modern Indian governments have suppressed the “truth” so much so that his argument can only be proven through “negative evidence”. To Oak’s credit, revisionism on the part of the Mughals is a fair assumption, yet his explanation of how such revisionism could have materialised is really problematic. On the one hand, he alleges that the hatred that Shah Jahan demonstrated for Hinduism led to the desecration of Hindu temples and the destruction of proof (such as Hindu artefacts) that would have proven the Taj Mahal’s true origin. Yet, Oak somehow rationalises that Shah Jahan’s “fanatical hatred for Hindu motifs” did not lead to the complete burial of Hindu symbols left over such as the “trident pinnacle”, as the “Muslims of those times did not know how to repair the crack (left over)”. Unfortunately for Oak, simplistic racist pandering and assertions do not count as proper analysis, and to that end, his argument detailing the revisionist tendencies of the Mughals is flawed and unconvincing.

Oak then turns to Indian academics and historians, and accuses them (along with Western academics) of historical revisionism due to their reluctance to deal with “a considerable professional loss of face and embarrassment” with the revelation of the truth. He singles out Western academics in particular and accuses them of being overly sentimental and “following a centuries old tradition of lustily alluding to Shah Jahan as the creator of the Taj”. In a typical Oak-esque tradition he backs up his arguments with racist assertions, claiming that the average Western visitor’s “mental calibre must be rated much below that of an average Indian” due to their “sentimentalism about sexual love”, thus reducing their reliability as academics. Abject racism aside, Oak has made one seriously flawed assertion: he conflates historians into one monolithic entity, with the assumption that all historians must defend, or are somehow invested in preserving the established historical narrative. The truth of the matter is that historians often disagree – even in the case of supposedly clear-cut cases like the Taj Mahal. Historian Wayne Begley, for example, argued in 1979 that the architecture of the Taj Mahal was deliberately designed so as to aggrandise Shah Jahan as a regal emperor capable of mirroring Paradise, and thus should not be taken as a mausoleum at face value[14]. In fact, historians are incentivised on numerous fronts to challenge the established narrative as far as possible. For one, simply agreeing with the status quo with no value-add whatsoever does not differentiate a historian or provide a “breakthrough” for one to advance their academic career. Academic journals are not likely to publish accounts that simply rehash what previous authors have said, thus providing a financial incentive for historians to challenge the norm as far as possible. As such, Oak’s claim to this regard is not really believable. He has not really provided tangible evidence of historians deliberately toeing the established historical narrative in the face of credible alternative theories (i.e. anything apart from Oak’s logic) and has ignored the historians who have credibly questioned the status quo due to the wealth of incentives that historians possess to do so in the first place. Thus, in my opinion, his claims of a “coverup” by mainstream academics simply does not hold true, and as such, does not justify him relying on “negative evidence” to prove his point.

Taking stock

In conclusion, I believe that I have dealt with the bulk of Oak’s claims regard the origin of the Taj Mahal. In my earlier post, I proved that Oak’s issues with the established narrative are not credible, and that his alternative “theory” simply does not stand on its own. His excuses for his argumentative and evidentiary gaps similarly do not hold up to reason and logic, and as such, should not be used to justify the assertions, generalisations and racist pandering which forms the core of most of his arguments. Oak’s theory is thus only useful as a reminder of the divisive and dishonest nature of historical revisionism, which must be avoided at all costs. At the same time, however, the academic community should not dismiss such claims without proper debate. Regardless of the inevitable headaches and face-palms that such theories invoke, such arguments can only be put to rest once they have been laid bare for public judgement and ridicule. A single historical critique is not enough to put Oak’s theories to rest, considering the extent of their proliferation in Indian politics and society at large. However, a decisive initiative by historians to set the record straight in the societies that they inhabit would be a start towards a world where our understanding of the past is not coloured by disingenuous introspection in the present.

References:

[1] Collier, D. (2016). The Great Mughals and their India. New Delhi, India: Hay House India.

[2] Koch, E. (2005). The Taj Mahal: Architecture, Symbolism, And Urban Significance. Muqarnas Online,22(1), 128-149. doi:10.1163/22118993-90000087

[3] Lowry, G. D. (1987). Humayuns Tomb: Form, Function, and Meaning in Early Mughal Architecture. Muqarnas,4, 133-148. doi:10.2307/1523100

[4] Richards, J. F. (1995). Shah Jahan 1628–1658. The Mughal Empire,119-150. doi:10.1017/cbo9780511584060.009

[5] Collier, D. (2016). The Great Mughals and their India. New Delhi, India: Hay House India.

[6] Mehta, M. (1991). Indian Merchants and Entrepreneurs in Historical Perspective. Delhi: Academic Foundation, 91-113

[7] Thevenot, C. (2012). Jean de Thévenot: Grand voyageur oriental, premier ethnologue français, révélateur du café à la Cour de France. Saint-Denis: Édilivre.

[8] The source for this incident was a European traveler by the name of Jean de Thévenot, who probably heard a recollection of the event at the court of Emperor Aurangzeb in the 1660s. The reliability of this source is thus questionable as Thévenot may have heard an exaggerated or distorted version of the incident. However, the fact that Thévenot heard about an event which censured Aurangzeb at his own court indicates that the story of the attempted conversion was true, at least in its outcome. While the details of the event itself could still be exaggerated, I thus do not think that Thévenot fabricated the event or the way it played out.

[9] Wee, M. V. (1988). Semi-imperial polity and service aristocracy. Dialectical Anthropology,13(3), 209-225. doi:10.1007/bf00253916

[10] Chandra, S. (2007). History of Medieval India: 800-1700. New Delhi: Orient BlackSwan.

[11] Aksan, V. H., Zürcher, E. J., & Roy, K. (2013). Fighting for a living: A comparative history of military labour 1500 – 2000. Amsterdam: Amsterdam Univ. Press.

[12] Faruqui, M. D. (2008). At Empires End: The Nizam, Hyderabad and Eighteenth-Century India. Modern Asian Studies,43(01), 5. doi:10.1017/s0026749x07003290

[13] Leonard, K. (1979). The ‘Great Firm’ Theory of the Decline of the Mughal Empire. Comparative Studies in Society and History, 21, 151-167. Retrieved February 21, 2018.

[14] Begley, W. E. (1979). The Myth of the Taj Mahal and a New Theory of Its Symbolic Meaning. The Art Bulletin,61(1), 7. doi:10.2307/3049862